an extract from The History of Moira yet to be published

As we move forward around 500 years, we discover more barbarous activity. Hoards came to fight in 637 AD and battled for six days. Hundreds of them never went home. This Battle of Moira is the earliest historical record of life here.

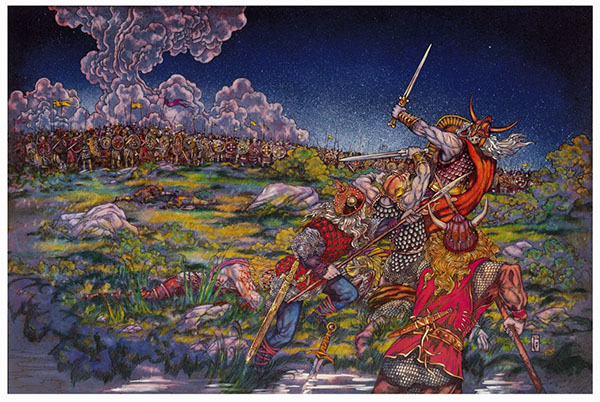

The Battle of Moira depicted by Jim Fitzpatrick

©Jim Fitzpatrick. Used by permission

Congal Cláen, King of Ulster had killed the King of Ireland in 628 but was defeated the following year at the battle of Battle of Dun Ceithirnn in Londonderry. Congal fled to Scotland and Domhnall of the Clan Connall became the new High King. In Scotland, Domhnall sought help from King Domnall Brecc of the Dal Riada, a Scottish kingdom that included northern Irish territories. He returned to Ireland with an army of Britons, Scots and Saxons, including a Scottish King and a number of Princes.

He quite probably arrived through Dunseverick. One of the five royal roads from Tara, seat of the Kings of Ireland, ran due north and ended at Dunseverick castle. This ancient road was known as Slige Midluachra or High King’s Road and it crossed the Lagan at a fort near Moira – probably over the ford where Spencer’s Bridge now stands. Congal and his troops marched south. Domhnall advanced from Tara, with an army of Irish chieftains and princes.

The two armies comprising fifty thousand men on either side, came together at Moira on 24th June 637. After six long days of fighting, Congal’s army was annihilated; Congal himself was killed and also a number of the Scottish Princes. The battle is described as one of the most bloodthirsty in early Irish History. Sir Samuel Ferguson considered it “the greatest battle, whether we regard the numbers engaged, the duration of the combat, or the stake at issue, ever fought within the bounds of Ireland”.

He wrote an epic poem in 1872.

Congal: A Poem in Five Books

‘My sins, said Congal, and my deeds of strike and bloodshed seem

No longer mine, but as the shapes and shadows of a dream

And I myself, as one oppressed with life’s deceptive shows,

Awaking only now to life, when life is at its close.’’

The routed armies fled over the Ford Ath-ornagh (Thornford or Thornbrook), up the ascent of Trummery, and in the direction of the Killultagh Woods, near Ballinderry. When the Ulster Railway was being built, great quantities of bones were discovered in the cutting close to the ruins of the Old Trummery and Tower. It is quite likely that they are those of men and horses killed in the battle. Rev. Henry W. Lett, writing in 1800’s, says: “At Mr. Waddell’s lime quarries have been found quantities of the actual bones of the natives long ago. This was their graveyard and the mode of sepulture was some form of cremation. After the corpse had been burned, the ashes and bones were placed in a small pot or urn, made of the plastic clay, so well known by the excellent bricks and tiles now manufactured with it, and turned mouth downwards on a flat stone in a hole in the ground about half a yard deep. And just below the kilns, exactly where it was possible to ford the Lagan River there stood a mound which a few years ago was discovered to consist almost entirely of human remains, bearing marks of calcination, evidently of those who had been slain in some great battle”.

Some of the names of the townlands in the area originate from the Battle – particularly Aughnafosker, which means the ‘field of slaughter’ and Carnalbanagh – the’ Scotsman’s grave’. There was once a pillar stone in Carnalbanagh with a crude cross and some circles on it. It marked the graves of the Scottish Princes. An elderly native of Moira claimed the pillar was in the centre of the ring fort at Claremont.

Sir Samuel Ferguson in his poem writes about that pillar-stone.

The hardy Saxon little recks

what bones beneath decay,

But sees the cross-signed pillar-stone,

and turns his plough away.

At the end of his book, Sir Samuel added a note concerning this stone.

I learn with deep regret and some shame for my countrymen of the North, that this memorial exists no longer. It has been destroyed by the tenant. I saw it, and was touched by the common humanity that had respected it through so many ages, when I walked over the battlefield, accompanied by the late John Rogan, the local antiquary of Moira, in 1842.

O’Donovan refers to a letter he received from the same John Rogan, in which he was told that the farmer who removed the stone “was named Green. He is not long dead.”

© David McFarland. Not to be reproduced without permission